In 2015, my interest was in making good decisions. For example, I was interested in joining a good engineering opportunity and buying a promising stock. So, I thought hard about making a few key decisions, like immigrating to the U.S. or purchasing a few stock shares. Many choices unfolded well in retrospect, but at that time, I felt uncertain about determining the succeeding steps and connecting the previous events.

As time passed, I believe my system evolved so that individual decisions could accumulate in a more cohesive direction. Moreover, I think the system is reasonably resilient and can withstand a few bad outcomes (just like the turmoil of the 2022 market). This system is strategic and much more powerful than a single decision. For example, I introduced the GAP framework to grow careers more effectively. In this article, I’m attempting to generalize the strategy for further expansions.

Categories for now 🔗

From a very simplistic perspective, life is a repetition of:

- Interpret the past.

- Predict the future.

- Act now based on the prediction.

In the end, we only control what we can do now.

Then, we can categorize the actions as below with examples:

- Capabilities: Expand what we can do.

- Speak a new language.

- Efficiencies: Improve how we take action.

- Set up a robotic vacuum to reduce the total cleaning time by half.

- Toils: Handle day-to-day operations to stay where we are.

- Change the diapers of your baby.

- Plan: Organize ourselves to determine how to manage the above actions.

- Determine to take an accounting class for the next three months.

- Buffer: Fill our lives beyond the above.

- Exercising, reading, and spending time with loved ones.

I found the framework useful as it applies beyond individuals: as you take larger roles in a group, you can expand the strategy beyond yourself, like managing a team or even a company. For example, as an engineering manager, I could use the framework to determine the next projects and resource allocations to maximize our strength for the long term. The framework helped the team to identify the next projects, prioritize among different types of projects to maximize value creation, and reduce distractions that sound nice but are too ambiguous for now. Recognizing and protecting the buffer is also important because that’s typically the first area reduced when a team is constrained.

Creating value 🔗

You can see that the first two actions (capabilities and efficiencies) add value directly while the next two types (toils and planning) can indirectly multiplicate the direct channels. For example, if you are overwhelmed by toils every day (e.g., your engineering team spends too much time handling pages), there’s no point in aiming for additional values, and you need to reduce toils at the highest priority. Likewise, spending too much time on planning can be counter-productive. You need to be courageous to directly add value rather than waiting for the perfect plans.

Most decisions should probably be made with somewhere around 70% of the information you wish you had. If you wait for 90%, in most cases, you’re probably being slow.

– Jeff Bezos (2016 Letter to Amazon Shareholders)

It is also critical to balance capabilities and efficiencies based on your circumstance. Let’s say you manage a business. If you focus too much on capabilities, you may increase revenue, but the underlying cost structure can threaten your survival – the market in 2022 is a good example where cash suddenly became restricted, and many companies had to lay off employees to manage the bottom line. Similarly, if you focus too much on efficiencies, your business may not grow fast enough to be relevant. Of course, the worst execution is spending too much time on irrelevant efforts. This is surprisingly common as we are easily distracted by ideas that sound nice but help neither capabilities nor efficiencies.

Durability and disruptions 🔗

When you have a durable structure, it is more straightforward to focus on creating value with little distraction and muda. This is more valuable for a larger group of people as the communication costs increase significantly for complexity. With an enduring structure, an org can scale to multiple departments and deliver goals in parallel (e.g., product teams can add more features while platform teams improve reliability). Sometimes, we see a great leader who provides a cohesive mission across the entire team, but this can only happen when the vision is meaningfully durable.

A truly great business must have an enduring “moat” that protects excellent returns on invested capital.

– Warren Buffett (2007 Letters to Berkshire Shareholders)

In rare cases, however, you need to make disruptive changes because nothing is permanent. For example, Warren Buffett mentioned that Wrigley had a durable business as the no.1 gum company in 19931. That was probably true, and no other gum-like products could compete against it, but smartphones disrupted the entire gum business out of fashion in the 2010s. There’s no perfect way to protect yourself against such Black-swan shifts, but you can still try small experiments to lower the risks of disrupting changes. And when you are reasonably confident, it is wise to disrupt yourself before others do. That can be a job change, immigration, or switching majors.

Application and iteration 🔗

The framework is useless if we cannot apply it to real life. So, while there’s no silver bullet, I think writing a few examples can help applications.

- As a software engineer, I categorized prospective projects to clarify anticipated values. Without clarity, I found myself mumbling different aspects of projects, confusing others. When I switch between capabilities, efficiencies, and toils, the message gets blurred, and it is hard to be funded. In contrast, clarity helps engineering projects initiate with broader support and course-correct when the underlying assumptions shift.

- As an engineering manager, I leveraged durable layers to deliver extra capabilities and bring efficiencies at a lower cost. The implicit durability helped me to plan for the future more reliably and drive long-term efforts. Unfortunately, some orgs may value more complicated solutions that are expensive to manage, and there’s nothing you can do. Still, we can use that as a great sign to start exploring other options and disrupt ourselves, like switching jobs.

- As a retail investor, I analyzed the businesses of prospective companies to determine if their structures can durably scale and balance different aspects to keep growing. The durable structure should enable increasing revenue for a long time with manageable CapEx and sublinear increases of OpEx, which can be a great company to purchase. I changed my position when my underlying assumptions were shaken.

- I simplified my personal life to reduce toils and distractions and protect enough time for different types of activities (e.g., reading, writing, and sleeping).

Because the framework applies broadly, leveraging other sources is a great way to reduce your risks (I wrote a few reviews for that seemed particularly helpful). Despite all the efforts, however, we will still face failures because the future is unpredictably unpredictable. So, we must revisit our contexts regularly, predict the future with more recent data, and adjust executions. With iterations, we can still attempt to reduce the damages of failures and maximize gains from successes. Eventually, regardless of individual results, I believe exploring our own paths is a meaningful way to live. ∎

Credit 🔗

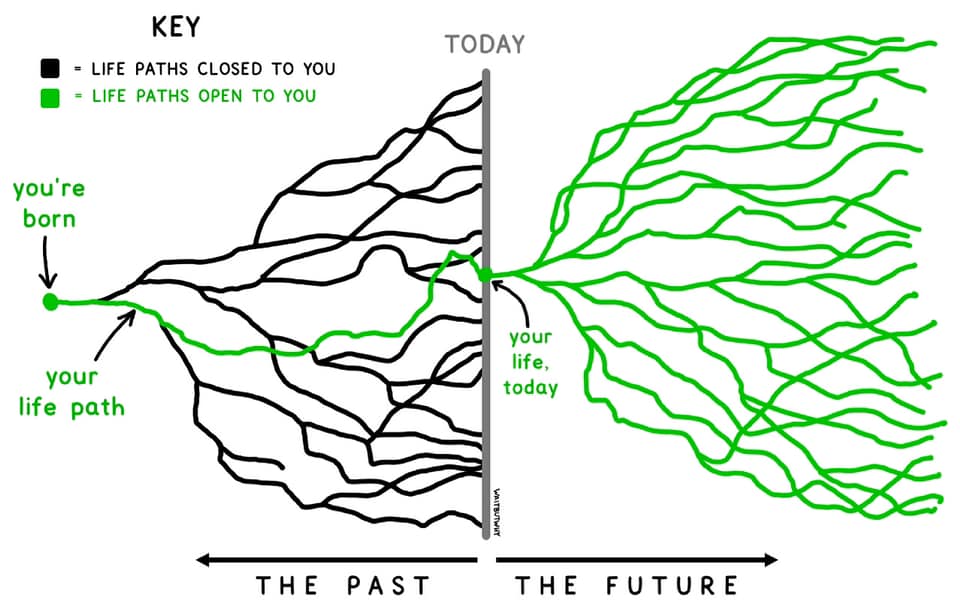

Wait But Why for a great visualization of past vs. future vs. now.

-

Warren Buffett talks about “durable competitive advantage” in 1993. ↩︎